Stakeholder Engagement and Design: Giving Voice to Vision

I have heard and have come to believe that, at our worst, we do things to people. Then, a little better, but not great, we do things for people. And, at our best, we do things with people.

It is an interesting way to think about the way we relate to stakeholders in design and construction projects for the community. We should aspire to design projects with the folks who will use and enjoy them, but unfortunately, not all projects go this way.

For example, if you enjoy the benefit of home ownership, you likely provide a great deal of input regarding the location and design of your home. But, if you rent or lease space, you probably have limited options thrust upon you. Design is done to you in this instance.

Similarly, if you live in a wealthy school district or attend a private school, you may be invited to provide input related to school design and amenities. But, if you reside in a lower-income district where school renovation or construction is driven by state funding, you likely have less options on what facilities you can have in your school. These decisions are made for you.

We strive to take our design processes beyond to and for and bring stakeholders into the process as co-designers who design with us in participatory design processes. We leverage our expertise with user insights to balance the aspirational side of a project with the practical side. We hear and understand what people appreciate and want, but it is our duty to embrace the excitement of the possible and bring it to reality.

With that in mind, it becomes incredibly important for design teams to hear and translate the desire to the “doable.” As professionals, we need to build consensus and support for a point of view and then leverage the power of multiple minds to build a plan of action to bring vision to life.

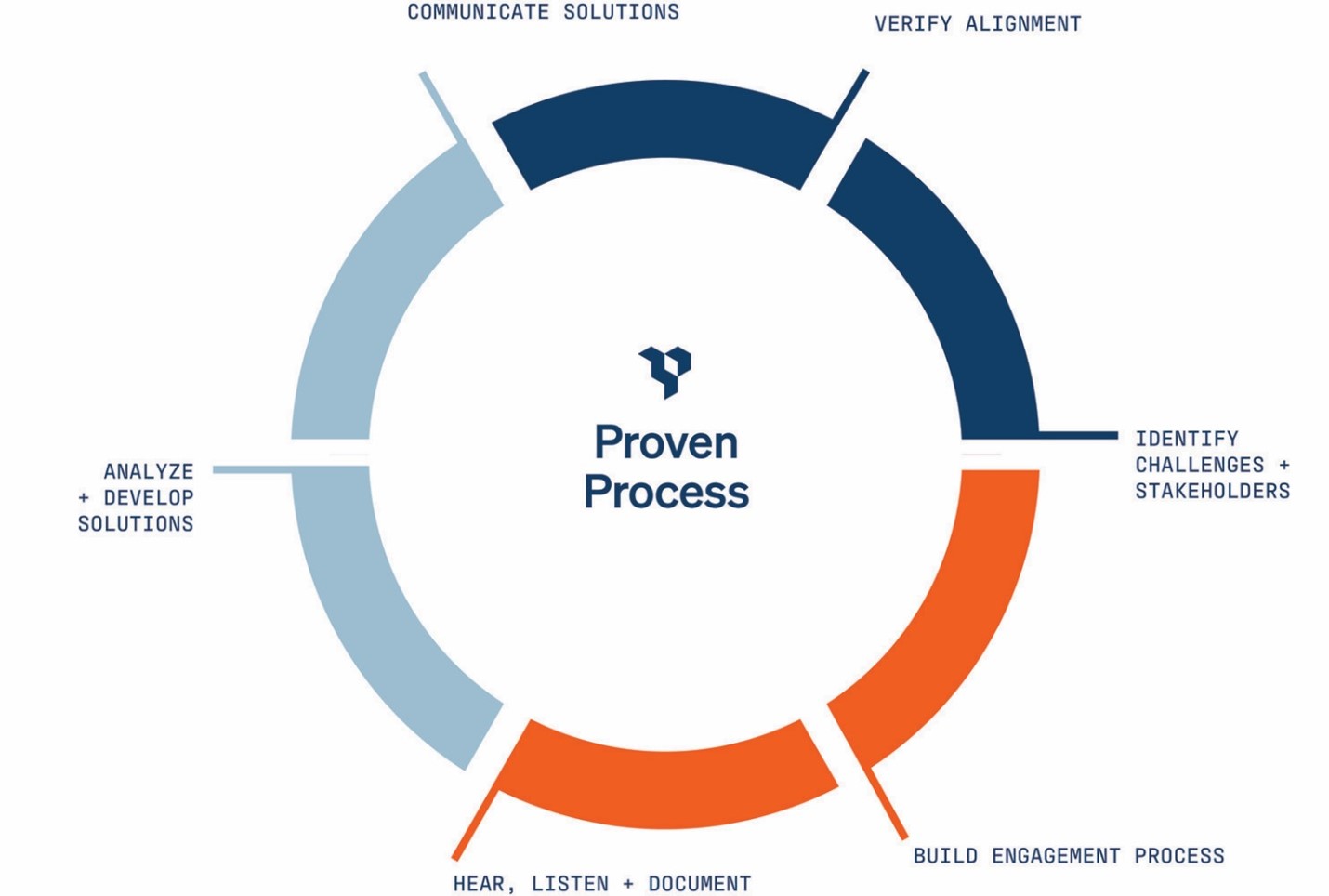

As you would imagine, empathy is a major theme in these developments. So, Triad has developed a process to enable our architects and designers to understand the issues building users face. We listen to understand what our clients want, and we work with stakeholders to identify challenges. In fact, 66% of our process is listening. And we repeat the listen, hear, document process as many times as necessary to verify alignment and identify solutions that satisfy and inspire our stakeholders.

Ours is a process that bars against pre-determined notions and works in favor of enriched group thinking. With it, we’re sure to lean into fresh perspectives instead of template approaches. It’s our opportunity to ensure that our work reflects the individuality and spirit of a community.

One example of the success of our process came through our work with Emma at Pointview Elementary in Westerville, Ohio.

As we collaborated with the Westerville City School District to convert a 1960s-era, open classroom concept, we envisioned something more modern and functional. But we also wanted to create something students could be excited about.

Enter Emma and the students of Pointview.

In our work to discover the district’s values and vision, we engaged the students who would be learning at the renovated building. The process uncovered a wealth of inspirational ideas that we turned into unique attributes, including:

- An entry space that displays the word, “Welcome” on its walls in 94 languages to represent the diversity of the district’s students and their backgrounds.

- A nautical theme that extends through the building with floor finishes and culminates in a lighthouse in the open media center.

- An Art room with an oculus that acts as a sundial, tracking the sunlight’s movement across the room’s floor.

- “Emma’s Glass Roof” – a circular opening in the oculus ceiling that represents the limitlessness of student dreams and educational opportunities.

“The school is something I can brag about when talking to new friends from other schools,” Emma told us. “I feel pride when talking about the new classrooms and MY glass roof!”

In a similar example, students in the Columbus City Schools District in Columbus, Ohio, helped Triad designers with a pilot project to replace furniture across the district. Children from 13 middle schools shared their ideas of inspirational spaces by creating mood boards, clipping photos, and modeling floor plans with scaled pieces of furniture.

The benefit was two-fold. Cafeterias and media centers across the district were renovated according to student preference. But perhaps far more importantly — the exercise demonstrated the importance of inclusivity and representation in architecture and design, as Black students in a majority Black district were empowered to influence decisions affecting their day-to-day schooling.

At Annehurst Elementary School in Westerville, students advocated for a tree house in their new school. We made these dreams come true, creating an extended learning space in the imaginary tree canopies of the new school. We even extended this theme of nature throughout the building. Speaking towards the balance I mentioned earlier, all of this was done on budget, on schedule, and satisfied the local building codes: aspirational and practical.

I think all of these are great examples of how stakeholder engagement can positively impact project planning. Broad perspective and differing points of view directly influence architecture, design, and functionality of community facilities. Even in instances where our stakeholders have expressed differing points of view, we’ve been able to use the process to help establish common ground, more thorough understanding, and build a stronger sense of community.

I am reminded of one community member at a public stakeholder meeting with Gahanna Jefferson Public Schools. We randomly grouped community members at tables and took them through several group exercises to discuss the planning of the new Lincoln Elementary School. What they didn’t know, is that they were going to elect a spokesperson to present their ideas at the end of the session. As one spokesperson stood up to present, he made sure everyone knew that he did not vote for the school Bond Issue and that the only reason he came to the meeting was to make sure that the speed limit didn’t get slowed down on his street. His commute to work every day already took too long. However, he went on to explain that he met some of his neighbors at the meeting for the first time and understood why they wanted the new school for their grandchildren. He explained in detail the careful planning that he and his other team members took to make sure that the path for the kids to walk to school and cross his street was safe. He was ready to reduce the speed of his street because it meant that the grandchildren of his new friends would be safe. Empathy leads to consensus.

So many of us have heard the adage, “Walk a mile in my shoes.” At Triad, it’s very often the basis of our engagement with community stakeholders who can help us bring the best to a project. We value our stakeholders’ vision and strive to build inspiring spaces that a community can be proud to live in and leave for future generations.

All in all, we’ve learned that diverse perspectives enable broader conversations that lead to better ideas. And we encourage this approach for all who are involved in architecture and design.